A renewal is taking place in science, an untelevised one. Tension has been building in recent years regarding the ‘puzzle’ that is scientific knowledge: most puzzle pieces are to be found outside the visible material realm; outside the laws of spacetime. Immaterial, uncrystallized worlds have other laws that can also be studied. The scientists who know this are finding themselves in a standoff with the dominant scientific school that for centuries has been proclaiming Ignoramus et Ignorabimus: we do not know and we will never know.

The work of Italian philosopher Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) marks the transition of one historical era into another: the gradual decline of the human ability to receive revelation through nature and the gradual rise of the Age of Ignorabimus. Thinkers before the 15th century had been more closely connected to an awareness of revelation through nature; the ability to see through nature and ‘read’ what it reveals. Logic emerged as a fundamental part of this.

Pico della Mirandola described that, on Earth, the rocks and minerals, the plants, animals and humans, do not originate from Earthly forces but are brought about by cosmic forces, and that humans are dependent on the star that stands over them; the human being is therefore a reflection, a natural revelation of the cosmic – a microcosm. If we want to investigate the nature of the human being, Pico della Mirandola explained, we must investigate the stars. At this point he stopped and said: it is not up to Earth-bound man to investigate the stars.(1) Pico della Mirandola voluntarily renounced the quest for the higher knowledge that he loved so much: Man should focus only on immediate causes instead of driving forces.

In the centuries that followed this particular scientific mood continued to evolve, until the work of thinkers like Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) and Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818-1896) formed a silently accepted axiom, an unprecedented dogma in science that dictates that only what five senses display can be the input for the scientific method, and what scientists can not know by these means, can never be known by anyone. Science is inherently restricted by ‘The Limits of Knowledge’; this is the title of one of du Bois-Reymond’s lectures from 1872, which he concluded with the word Ignorabimus. We will never know.(2)

Today, this dogma has lead to an impasse. Scientists are disillusioned by the continued lack of results and the persistence of irreconcilable contradictions. A handful of honest thinkers dares to speak up about this scientific standstill, which is now turning into a chaotic standoff. Last year, linguist Noam Chomsky criticized the world’s most prominent scientists: “What they say fancifully is ‘we’ve come to understand something about the puppet and the strings, but we have nothing to say about the puppeteer’. It’s just a total mystery. And that’s where we live.”(3)

In the 1950s, biophysicist Wilhelm Reich (1897-1957) had described this as “knowing the very last details about motors but knowing nothing about how to make them run.”(4) There have been many more thinkers to express this, like Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) and others. Chomsky went on to say, “Maybe it’s beyond cognitive capacities, if so we would be unique.” Pico della Mirandola had said: We are unique, but we must not investigate this uniqueness. Chomsky says: We can not investigate, thus we may be unique. A scientific age has come full circle.

The Age of Ignorabimus was a necessary and fruitful time, yet also a cold and painful time for countless thinkers with advanced cognitions such as Goethe, Nietzsche, Tolstoy or Reich. We must now awake, scientists today conclude, from the long, deep sleep that ensued from the belief that we will never know.(5)

Our ancestors had a whole other awareness, namely, that knowledge requires the inner conscious ability to receive it at the right time and the right place; that we have to prepare and strengthen our character before we can evolve and progress through appropriate ideas, insights, inspirations, revelations or epiphanies; that, if we have the will to know something, we will first need to ensure that our evolving consciousness is mature enough to receive new knowledge.(6) This goes against almost everything our modern age represents and promotes.

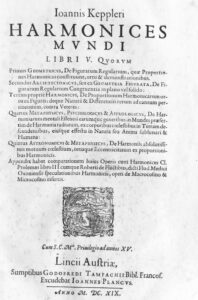

Some of the greatest thinkers in history embodied a scientific mood that acts as an antidote to the current Age of Ignorabimus, namely, the scientific mood of humble receptivity. This was the mood that, for instance, the German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) embodied, who wrote in 1619:

O qui lumine Naturae desiderium in nobis promoves luminis Gratiae, ut per id transferas nos in lumen Gloriae; gratias ago tibi Creator Domine, quia delectasti me in facturâ tuâ, et in operibus manuum tuarum exultavi: En nunc opus consummavi professionis meae, tantis usus ingenii viribus, quantas mihi dedisti; manifestavi gloriam operum tuorum hominibus, istas demonstrationes lecturis, quantum de illius infinitate capere potuerunt angustiae Mentis meae; promptus mihi fuit animus ad emendatissime philosophandum: si quid indignum tuis consiliis prolatum a me, vermiculo, in volutabro peccatorum nato et innutrito, quod scire velis homines: id quoque inspires, ut emendem: si tuorum operum admirabili pulchritudine in temeritatem prolectus sum, aut si gloriam propriam apud homines amavi, dam progredior in opere tuae gloriae destinato; mitis et misericors condona:

O thou who, through the light of nature, awakens in us a desire for the light of grace, in order to lead us through it to the light of glory, I thank you, Lord and Creator, that you have delighted me with your creation and that I have rejoiced in the works thy hands; behold, I have now finished the work of my calling, utilizing the measure of strength thou hast bestowed upon me; I have revealed to men the glory of thy works, as much as my limited mind could grasp of thy infinity. If anything has been presented by me that is unworthy of thee, or if I have sought my own honor, graciously forgive me.

~ Johannes Kepler, 1619, Harmonices Mundi (7)

(1) Pico della Mirandola, Giovanni. Disputationes adversus astrologiam divinatricem. Bologna, 1494. Cited in: Steiner, Rudolf. „Mysterienstätten des Mittelalters“ lecture 3, Dornach, January 6, 1924.

(2) Du Bois-Reymond, Emil. Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens (On the Limits of Knowledge), lecture in Leipzig, 1872. (Digital edition)

(3) Chomsky, Noam. In: Naidu, Tevin. “Noam Chomsky: Do We Have Free Will? Moral Responsibility & The Meaning of Life”, a YouTube podcast published December 28, 2024.

(4) Reich, Wilhelm. The Murder of Christ. Volume I of Wilhelm Reich Biographical Material. History of the Discovery of the Life Energy. The Emotional Plague of Mankind. Orgone Institute, Rangeley, Maine, 1953. pp. 50.

Or for example: Leo Tolstoy, On Life and Essays on Religion, Oxford University Press, London, Humphrey Milford, 1934. (First published 1887)

(5) Hoffman, Donald D. The Case Against Reality. How Evolution Hid the Truth from our Eyes. Penguin, London, 2019.

Side Note: Spiritual science counts twelve human senses instead of five, six inward and six outward.

(6) There are many examples but, for instance, Plato and his aphorism “all knowledge is remembering”.

(7) Kepler, Johannes. Harmonices Mundi. Libri V, lib. V, ch. IX. In: Gesammelte Werke, vol. VI, München, 1940. pp. 362-363.

Written by Laura M. Slot, historian and writer with a focus on outsiders in twentieth century intellectual history lauraslot.com

Citations and translations are encouraged if accompanied by a reference to this blog article.